Who among us has not sometimes mused about how convenient it would be to upgrade or alter our bodies? I myself have occasionally pondered the benefits of a nuclear-powered exoskeleton strong enough to crush human skulls like eggshells (this would facilitate opening recalcitrant pickle jars).1 Unsurprisingly, SF authors have also thought along those lines. In particular, the mid-to-late 1970s saw what seemed like a flurry of SF books exploring the possibilities of advanced body modification.

I have no idea if this was actually a trend or simply accidental clustering. Thematically consistent with the other self-improvement efforts of the so-called Me Generation, it certainly seemed like a trend at the time. Take, for example, this cluster of books encountered in the mid-1970s…

Cinnabar by Edward Bryant (1976)

In the very distant future, the city of Cinnabar may be found between the desert and the ocean. Cinnabar may be the last city left on the world. Certainly, visitors from outside are not expected. This would be a sad, forlorn reality…if the sybarites of Cinnabar were at all inclined to consider the state of their world.

Cinnabar’s people have access to sophisticated technology that is the stuff of science fiction to us. Therefore, many facets of self (body and mind) that we can currently change only with great effort (or cannot change at all) are a matter of fashion in Cinnabar. It would be wonderful if this meant a golden age of self-realization. What these people actually do with their potentially liberating technology: create stark class differences, abuse others, and embrace joyless decadence.

Miraculous technology is wasted on some people, as the people of Cinnabar amply demonstrate.

Cinnabar was inspired in part by Ballard’s Vermilion Sands. It seemed to me that Ballard’s characters seem to have more fun (in a repressed British way).

Don’t Bite the Sun by Tanith Lee (1976)

The domed cities of Four BEE, Four BAA, and Four BOO are oases in a world desert (just as Cinnabar is isolated in an arid world). No oceans. Each city is self-sufficient and, aside from sporadic contact with the other cities, inwardly focused.

Young people—the Jang—are encouraged to embrace hedonism, enabled by the fact that physical form is a matter of personal taste. Even death is no major inconvenience, for “life sparks” are easily transferred from corpses to new incarnations. For people willing to settle for mindless pleasure, it is utopia. People who, like the narrator, seek a more meaningful existence will soon discover the limits of what is permitted.

Social convention is a powerful force in the domed cities; of the many pleasures one might enjoy, only a few are actually chosen. Assignations are always preceded by short and meaningless marriages. Couplings are expected to join one male body to one female body (to the extent that choices in bodily form can be described that way). This seems like an odd way to run a free love dys/utopia.

Man Plus by Frederik Pohl (1976)

Terrestrial Armageddon appears inevitable. For humanity and its creations to survive, Martian colonies are required. This would be no problem if Mars were the habitable Mars of old-timey SF. Mars being the nearly airless, radiation-soaked deathtrap that it actually is, to dispatch conventional humans there would be to doom them.

Enter Roger Torraway, the lucky individual who has been voluntold to test exciting new advances in cyborg technology. Accepting his new, heavily modified form will be a challenge. Once on Mars, Roger and all those dependent on his success will come to appreciate the utility of his transformation.

There are many SF stories in which the world faces some anthropogenic doom that everyone agrees is undesirable and nobody seems to be able to do anything about. Where do SF authors get their wild ideas? In this case, there are other factors influencing human behavior, factors whose natures and extent is not made clear until the conclusion of the novel. The characters will never know that they are not entirely responsible for their choices.

The Ophiuchi Hotline by John Varley (1977)

Centuries after the alien Invaders conquered the Earth, human civilization is thriving…in space. With the notable exceptions of Jupiter and Earth (both controlled by the Invaders), the Solar System is a human domain.

This is possible because the technology exists to reshape bodies at will, whether on a merely cosmetic scale or with more dramatic alternations that turn even Venus’ surface into a shirt-sleeve environment for humans. Many of the tools needed to prevail in the post-Invader reality were retrieved from the so-called Ophiuchi Hotline, an alien communications network into which humans have been tapping. Unbeknownst to humans, there is a charge for the information and that bill has come due.

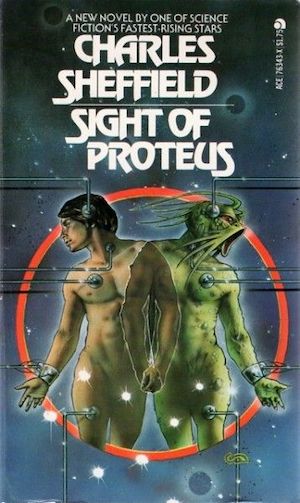

Sight of Proteus by Charles Sheffield (1978)

General Coordination struggles to keep overcrowded, resource-strapped Earth functioning. Their task is complicated by the ubiquity of Form Change, an advanced biofeedback technology that allows people to reshape their bodies as they see fit. Some forms place more demands on infrastructure than others, thus a need to steer the masses away from (for example) changes that would greatly increase lifespan and thus accelerate population growth.

Behrooz Wolf and his partner John Larsen investigate Form Change abuse. Their final three cases illustrate just how powerful Form Change can be in the hands of a sufficiently unscrupulous researcher, while illuminating certain aspects of Solar history heretofore underappreciated by humanity. Long ago, aliens called the Solar System home and while they are long dead, their relics are still quite puissant.

Biofeedback was a big deal back in the disco era. In fact, this Sheffield novel is rich in dubious obsessions briefly fashionable at the time, from the Population Bomb to all-powerful biofeedback to the works2 of Ovenden and Van Flandern. Sheffield was known as a hard SF author; his fans might be interested to discover this side of his work.

***

There are, no doubt, other disco-era works along these lines that I could have mentioned. Hansen’s War Games, for example, was only omitted because, being published in 1981, it seemed a bit too late for my purposes. Feel free to mention other example in comments, which are, as ever, below.

In the words of fanfiction author Musty181, four-time Hugo finalist, prolific book reviewer, and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll “looks like a default mii with glasses.” His work has appeared in Interzone, Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis) and the 2021, 2022, and 2023 Aurora Award finalist Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by web person Adrienne L. Travis). His Patreon can be found here.

[1]Did I get an exoskeleton from my doctor? No, I was told about “corneal scarring” and told to use artificial tears. Artificial tears are the carob of personal enhancement technology.

[2]Van Flandern in particular was an energetic source of non-consensus scientific models.

Behrooz Wolf is (of course) usually called Bay Wolf.

One must, of course, list Martin Caidin’s Cyborg, the novel upon which the television show The Six Million Dollar Man (and its sequels) was based. It’s even from 1972, so fits the bill perfectly.

Steve Austin would cost $43,544,928.23 today, which doesn’t scan quite as well. Might as well just go for Six Billion and be done with it. When is that reboot coming, anyway?

you have the Martin Cardin’s Cyborg and it’s sequel (on my mind because I just read Robert Hampson’s The Moon and the Desert)

“Ballard’s characters seem to have more fun”? How often would you use that sentence? ;-)

I have yet again forgotten the title and author of one or more books, minor perhaps, about a superannuated interstellar super-soldier/spy who is basically X-Men’s Wolverine, or at least he has mechanical pop-out claws as well as other cyborg goodies. So, maybe from the 1970s?

The antihero in Alfred Besters “Tiger Tiger” got himself quite heavily upgraded in the later part of the book.

It’s neither a novel nor from the 1970s, but I still feel as if I should mention Frederik Pohl’s “Day Million”. When it was discussed in Jo Walton’s 1967 Hugos post Gardner Dozois said

Arthur C Clarke’s A Meeting with Medusa is from 1971 and features a protagonist, Howard Falcon, who one-ups Steve Austin just a bit.

Samuel Delany’s Babel-17 features extensive body modification, mostly for recreational purposes (at least, I can’t think of any practical applications for having a small dragon installed in your shoulder.)

The Masters in David Bunch’s “Moderan” stories enjoy near-total cyborgization, with only a few “flesh-strips” remaining of the human body. (Well, I say “enjoy”, but what really makes them happy is constant total warfare. I’m not sure it’s healthy.)

Bernard Wolfe’s Limbo (sometimes known as Limbo-90) involves the “vol-amp” (voluntary amputation) movement, in which people have their limbs removed in what’s meant to be a very literal disarmament process. Sadly, a lot of its members rather miss the original spirit of the thing, and replace their missing limbs with a variety of useful prosthetic upgrades, e.g. arm-mounted flamethrowers. The book’s been cited as an influence on the development of the Cybermen for Doctor Who.

I’m going back well before disco, so let’s go back even further and mention Neil R. Jones, and The Jameson Satellite and its sequels, in which the late (very late) Professor Jameson is revived and upgraded by the Zoromes, who remove all extraneous bits such as his body and install his brain in a robotic chassis. Jameson is surprisingly OK with this development. (Come to think of it, Lovecraft’s “Mi-Go” do much the same in “The Whisperer in Darkness”. And then there’s Edmond Hamilton’s “Captain Future”, featuring Simon Wright, one of the Captain’s mentors, who is a disembodied brain in a box.)

I can remember reading Keith Laumer’s “A Plague of Demons” in which our hero – voluntarily – goes through a variety of bodily modifications, whilst investigating some mysterious disappearances, finally ending up – involuntarily – as a disembodied brain, operating an alien war machine, along with a wide variety of other humans, harvested over a considerable period of time for the same purpose – a tactic which the aliens come to regret.

2, NomadUK: Martin Caidin wrote three hardcover sequels to Cyborg, namely Operation Nuke, High Crystal, and Cyborg IV.

Other authors penned paperback tie-in novels based on the Six Million Dollar Man TV series–based, I gather on teleplays–and a couple of Caidin’s sequels were packaged in this series.

Pat Cadigan’s “The Girl-Thing who Went Out for Sushi” is the nicest story about extreme body modification, ever.

@8 — Thank you for plugging Moderan so I don’t have to.

The earliest and some of the most extreme body-mod SF I can think of (unless you count things like Hamilton’s “The Man Who Evolved”) is in Simak’s City, where people (and a dog) are modified way beyond Man Plus and Varley’s Nine Worlds: they become creatures capable of thriving on the surface of Jupiter, and find that they like it much better than their human bodies, leaving the Earth to robots, uplifted dogs, and (if I recall correctly) rapidly-evolving ants.

higgins@10: Yes, he did. And I read them all!

Frederik Pohl’s Man Plus also involves the Cold War – giving us a two-for-one hit on the 5 Books lists.

@8- well, I want a small dragon on my shoulder; that should be utility enough. I believe that the pilots’ massive modification is implied as necessary for their jobs. I also recall smaller mods being useful- such as a stellar calculator built into someone’s hand.

I love how the body mod techs in Varley’s world are the equivalent of today’s auto mechanics/tattoo artists- no years of medical school for them!

Marvel Comics got into the act with the 1970s series Deathlok the Destroyer.

@2 – There are lots of predecessors of Cyborg, some even from the 19th century; for example, the short story The Ablest Man in the World (1879) by Edward Page Mitchell featured a character who had a tiny clockwork Babbage engine implanted in his brain (which would otherwise be moronic) to make him a perfect logical thinker. There was also a 1964 predecessor of Cyborg which has some notable similarities – Adam M-1 (1964) by William C. Anderson, in which the brain of an astronaut is transplanted into a robot body.

@8 – I seem to recall that the shoulder dragons could be used to light cigarettes, so not completely useless.

I’m trying to remember a short story (novella?) by Frederick Pohl, I think. Humanity spread through the stars not by adapting new worlds to themselves but by adapting themselves, drastically in some cases, to new worlds. The story focuses on human beings who are effectively microscopic (as in about the size of diatoms) and live in small pools of water, and their battles with the local microfauna using other microfauna as riding stock.. I read this decades ago (early ’70’s maybe) so it’s possible that most of the foregoing information is wrong, but if anyone knows the story, I’d be glad to know the title.

@17: It’s “Surface Tension“, by James Blish.

#18 got the title of the most famous story in the series correct, but I just thought I’d add that “Surface Tension” was part of a series called “Pantropy”.

@Robert Carnegie, #4:

This sounds like it might be Archie Shellman, a clawed cyborg martial artist who makes a minor appearance in Roger Zelazny’s Roadmarks. Which was published in 1979. So, indeed.

Simak’s “Desertion”, one of the all time most frequent “what was that story?” requests back in the golden age of Usenet.

Eric, Niven’s brain-in-a-ship from “The Coldest Place” as well as McCaffrey’s _Ship Who Sang_ and sequels all seem to fit, albeit taking things to extremes.

Because she is such a great and iconic character, I would really really like to mention razorgirl cyborg Molly Millions, whom I first met in William Gibson’s short story “Johnny Mnemonic” and later in his classic novel _Neuromancer_. But since those works did not appear until 1981 and 1984, respectively, Molly is a bit outside the relevant time period. Therefore I will exert heroic self-control and avoid mentioning her. Nope, not even obliquely.

@8 Steve Wright: “Edmond Hamilton’s “Captain Future”, featuring Simon Wright, one of the Captain’s mentors, who is a disembodied brain in a box.” IIRC, S.J. Perelman wrote a hilarious piece called “Captain Future, Block That Kick!” in which Simon Wright figures.

Back in the 70’s I picked up a reprint of a 50’s (?) novel about all of humanity being turned into machine people. Not robots, but mechanical people. It was a “wake up to find out that your a machine” situation with explanation why. They did turn back into people, though a few might have been worse off, as they either “repaired” themselves with parts they found or augmented themselves. I don’t remember the title or the author, just the story. It’s probably somewhere in my collection…

Long before the stories cited, there’s Cordwainer Smith’s short story “Scanners Live in Vain”, wherein the eponymous scanners, and the convict laborers they supervise, have undergone the haberman process, a surgical procedure to sever almost all sensory nerves so they can work in space. Published in 1950, and possibly the only reason the SF magazine Fantasy Book is remembered.

Smith hints at body mods in some of his other stories, generally so that humans can adapt to conditions on worlds they’ve colonized. We meet one of the more extreme examples as a villainous cameo in one scene of Norstrilia. The underpeople, of course, are also the product of extensive genetic modification and body modification.

PamAdams @14 “I love how the body mod techs in Varley’s world are the equivalent of today’s auto mechanics/tattoo artists”

Today’s body mod techs are tattoo artists – witness Steve Haworth and magnetic implants!

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Implant_(body_modification)#Magnetic_implants)

the short story The Ablest Man in the World (1879) by Edward Page Mitchell featured a character who had a tiny clockwork Babbage engine implanted in his brain (which would otherwise be moronic) to make him a perfect logical thinker.

Read this and thought “this sounds like exactly the sort of thing which would interest that Forgotten Futures chap” only to find that it was posted by, indeed, that Forgotten Futures chap.

(Great game, by the way. Got us through lockdown. Team crashed after their gyrocopter’s ducted-fan engine ingested a pterodactyl and ended up having to levitate off the plateau using yogic flying techniques.)

The Ousters, from Simmon’s Hyperion Cantos, also come to mind.

Bruce Sterling’s Schismatrix has all sort of body-modding, including a woman who has her flesh lining the corridors of a hollowed out asteroid, iirc.

And Greg Bear’s Queen Of Angels and / have a bit going on using nanotech

14. PamAdams, no, it’s a small dragon *in* your shoulder. The joint is transparent. The dragon is controllable with practice. It can flap its wings and spit sparks. I think the sparks stay inside the shoulder.

You don’t get bodies more heavily modified than Jack Chalker’s “Well World” series.

@32 Mentioning Chalker would have been unsporting as the whole column could easily have been made up of Chalker’s books.

Five Jack Chalker Novels Without Body Modification could be challenging…

@34 I can’t even come up with one.

Theodore Sturgeon, of course comes to mind with “Venus Plus” and “More Than Human” while not strictly body mods do reference human morphology. In the Outer Limits episode “The Architects of Fear” a group of scientists perform surgeries on Robert Culp to create an alien in an attempt to frighten the Earths governments into joining forces against a common threat ala Ronald Reagan. Robert Duval received a similar treatment in the episode “Chameleon” but for different reasons. The Twilight Zone had some memorable episodes along these lines. One was to make old people look younger, another was to make a young woman conform to socially accepted concepts of beauty.

a group of scientists perform surgeries on Robert Culp to create an alien in an attempt to frighten the Earths governments into joining forces against a common threat ala Ronald Reagan.

I know what you mean here, but it is much funnier to read it wrong, not least because it reminds me of the Douglas Adams story “Young Zaphod Plays It Safe”.

A more recent book would go into this category as well. Pierce Brown’s first book in the Red Rising series the main character, Darrow has to go through extensive body modifications in order to infiltrate the gold class of citizens which a rebel group is trying to take down.

Iain M. Banks’ Culture series’ Culture citizens were descended from several humanoid races that had been melded together by ‘gene-fixing’ (germ-plasm genetic manipulation) and, in the process, got internal glands secreting recreational and utility drugs at will,along with volitional sex-changes. In a later book—is it Matter?—a character’s boss has been modified to have many mechanical limbs, and we’re informed (with a whiff of retconnerie, though not too much for my tastes) that The Culture goes through fads of extreme body-modification followed by periods in which a bog-standard–humanoid predominates.

(Iain “no-‘M'” Banks’ books beyond The Wasp Factory and Complicity, the ones I’ve read, seem to me likely to contain a lot of body-modification about which I’d likely rather not read, a matter of taste.)

tbh, the first story that came to mind when I saw the title of this post was Heinlein’s “I Will Fear No Evil” (1970), which is less body mod than body replacement – consciousness transfer is certainly not an uncommon concept for exploration in SFF, but that story sticks with me more than most.

I vaguely remember (probably mercifully; it wasn’t a very good novel, even to the kid I was back then) a novcel about an alien who lands on earth, but no one can even get near him/it; he’s just TOO fast. His reflexes are like lightning. Two brothers (ISTR they were twins), though, are recruited by The Government, and enhanced. One brother was normally-abled, and one brother (accidsent?) had his mind, but his body was pretty much non-functional. One of the brothers gets stationed on an asteroid, and he exhibits all sorts of nifty physical things, and the other brother is introduced to the reader in a bar, where someone sneaks up on him and in less than a second, he turns and fires three shots grouped very neatly on the sneaker’s heart. Oh, and he could also shoot 36 for 18 holes of golf.

He’s the one who meets the alien in his lair, and it turns out his reflexes ARE sufficient to best the alien (they engage in a bit of karate-like fighting). Who, I (mis)remember becomes an actual “good alien”. He just needeed someone who could communicate with him on his level. By the way, the brother who accomplished this was (obviously, even to me as a kid) the brother that was totally paralyzed/non-func tional. Turns out. that, in order to do all the mods mecessary, there had to be essentially noghint there to start with.

Does this jog any memories?

The article doesn’t mention Anne McCaffrey’s RESTOREE, which was about women who were skinned and given an entirely new outside appearance with new skin, and the only way they could tell that this had happened to them was a seam on the bottom of their feet. This was revelatory for me when I was a teenager in the 70s. Also Tantith Lees Electric Forest and some of her other books also deal with women’s bodies and expectations of perfection.

In Elizabeth Moon’s Vatta’s War series, many varieties of modified humans are generically called humoids. They show modifications like having two hands growing out of one wrist. And a shopping bag emerging from the other arm. That was only one example.

Some local religions were actively prejudiced against humoids.

No mention of Zelazny’s Creatures of Light and Darkness? The opening sequence, the inhabitants of the world Blis, the immortal Marduk’s eye, the “gods” Osirus & Anubis-lots of body mods.

Neal Asher is a master of this theme.

They show modifications like having two hands growing out of one wrist. And a shopping bag emerging from the other arm.

Is this… a serious book?

Iain “no-‘M’” Banks’ books beyond The Wasp Factory and Complicity, the ones I’ve read, seem to me likely to contain a lot of body-modification about which I’d likely rather not read, a matter of taste.

(winces) yes, you may have started with the wrong two books there. Those are definitely the nastiest by some distance. The Crow Road, Espedair Street, The Bridge and Whit are the best of the non-M books, and none, as far as I remember, have any body modifications at all other than the occasional earring. Fair amount of sex and violence, mind.

Maybe someone will remember this story. There are frequent changes in how women ought to look– fashion changing, not official tyranny. Women generally get a superficial makeover, but there’s one woman who’s the lead for the advertising who’s completely (and permanently?) made over. I think the story was told from the point of view of a man who loved the way she looked previously.

The Silver Metal Lover by Tanith Lee– the viewpoint character is a young woman whose mother imposes a modification on her to be plump(?) and copper-haired, but when the young woman leaves home, she reverts to her natural state of being thin and blonde.

Arthur Bryan Cover had a series (Included The Platypus of Doom about a future where there was a lot of body modification and, as I recall, nothing worth doing, rather like Lee’s Don’t Bite the Sun.

If @40 is going to open the door to body replacement in addition to modification we can easily include John Scalzi’s OLD MAN’S WAR, though I guess if we include the BrainPal there’s mods from early on. As you go on into the universe via its sequels there’s some more body mods here and there though it is rarely foregrounded.

That does make me think of Dietz’s “Legion of the Damned” series; there’s not much more extreme of a body mod than a brain in a box you can slot into different things.

With regard to 41, the story was written by Randall P Garrett and produced in book form under the title “Earth Invader”, although it originally appeared in magazine format under a different name.

I have also been reminded of a novel, “The Caves of Karst”, by Lee Hoffman, about a human diver, working on an Earth colony, who has been given a gill transplant to aid his work, only to face discrimination for his modification as have many other “modified” people.

@@@@@ 46, ajay:

They show modifications like having two hands growing out of one wrist. And a shopping bag emerging from the other arm.

Is this… a serious book?

The Vatta’s War books are a serious series. Moon mentions humoids casually, as part of her world building. They are shown as able to change features like specialized arms quickly and casually. It’s not as though a shopping bag would be a permanent choice.